SSH tunneling or SSH port forwarding is a method of creating an encrypted SSH connection between a client and a server machine through which services ports can be relayed.

Local SSH Tunnel with Port Forwarding

You can use a local ssh tunnel when you want to get to a resource that you can’t get to directly, but an ssh server that you have access to can. Here are some scenarios.

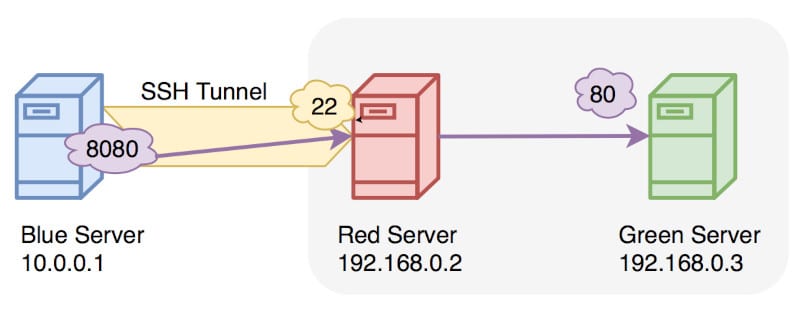

Proxy to Remote Server

In the image above, the blue host cannot reach http://192.168.0.3 but can ssh to 192.168.0.2. The following ssh command executed on the blue host will allow the blue host to reach the red host.

ssh -L 8080:192.168.0.3:80 reduser@192.168.0.2Code language: CSS (css)Now the blue host can open a browser, go to http://localhost:8080, and be presented with the webpage hosted on 192.168.0.3.

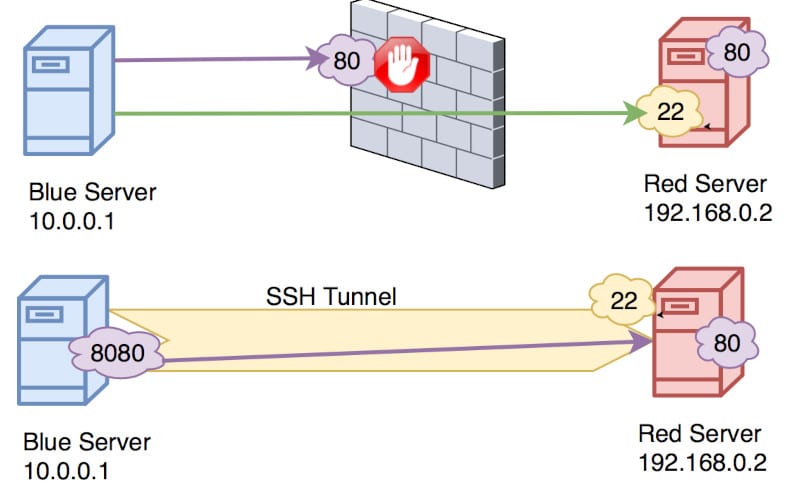

Local Port Forward

In the image above, the blue host wants to connect to the red host on port 80 but there’s a firewall in between which is denying this. Because the blue host can ssh to the red host, we can create a local port forwarding ssh tunnel to access that port.

The command on the blue host will be:

ssh -L 8080:192.168.0.2:80 reduser@192.168.0.2Code language: CSS (css)Now when the blue host opens a browser and goes to http://localhost:8080 they will be able to see whatever the red server has at port 80.

Local Port Forwarding Syntax

This syntax to create a local ssh port forwarding tunnel is this:

ssh -L <LPORT>:<RHOST>:<RPORT> <GATEWAY>Code language: HTML, XML (xml)Remote SSH Tunnel with Port Forwarding

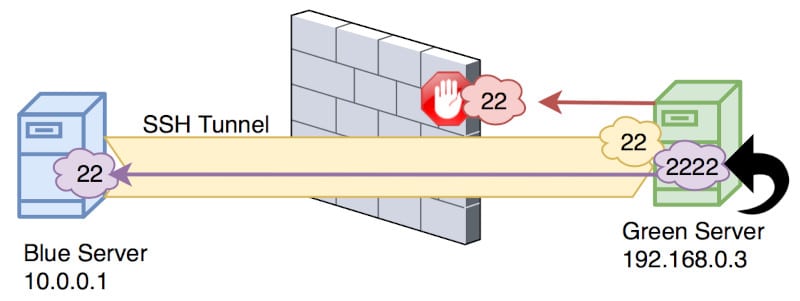

In this scenario, we are creating a reverse ssh tunnel. Here we can initiate an ssh tunnel in one direction, then use that tunnel to create an ssh tunnel back the other way. This may be useful for when you drop a drone computer inside a network and want it to “phone home”. Then when it phones home, you can connect to it through the established ssh tunnel.

We are on the green host and want to ssh to the blue host. However, the firewall blocks this connection directly. Because the blue host can ssh to the green host, we can connect using that, and when the green host wants to ssh back to the blue host, it can ride along this previously established tunnel.

The blue host initiates an ssh tunnel like this:

ssh -R 2222:localhost:22 greenuser@192.168.0.2Code language: CSS (css)This opens port 2222 on the green host, which is then port forwarding that to port 22 on the blue host. So if the green host were to ssh to itself on port 2222 it would then reach the blue host.

The green host can now ssh to the blue host like this:

ssh -p 2222 blueuser@localhostCode language: CSS (css)Using the -N Option

When using ssh, you can specify the -N flag which tells ssh you don’t need to send any commands over the ssh connection when it’s established. This option is often used when making tunnels since often we don’t need to actually get a prompt.

AutoSSH

The autossh command is used to add persistence to your tunnels. The job it has is to verify your ssh connection is up, and if it’s not, create it.

Here is an autossh command which you may recognize.

autossh -N -i /home/blueuser/.ssh/id_rsa -R 2222:localhost:22 greenuser@192.168.0.3The -i /home/blueuser/.ssh/id_rsa option says to use a certificate to authenticate this ssh connection.

Now when your tunnel goes down it will automatically try to reconnect and keep trying until it is successful. To make it persistent through a reboot, add the ssh command as a cron job.